As the holidays come to a close and the bright green, red, white and gold of Christmas slowly fade from the foreground of our lives, I have taken the time to reflect on a similar range of colors that has largely been ignored and has always stayed in the background of public consciousness. I experienced these hues during BAN Toxics’ visit to a few mining communities in Camarines Norte last October and discovered a whole spectrum of color that shines a light on life in artisanal and small-scale gold mining.

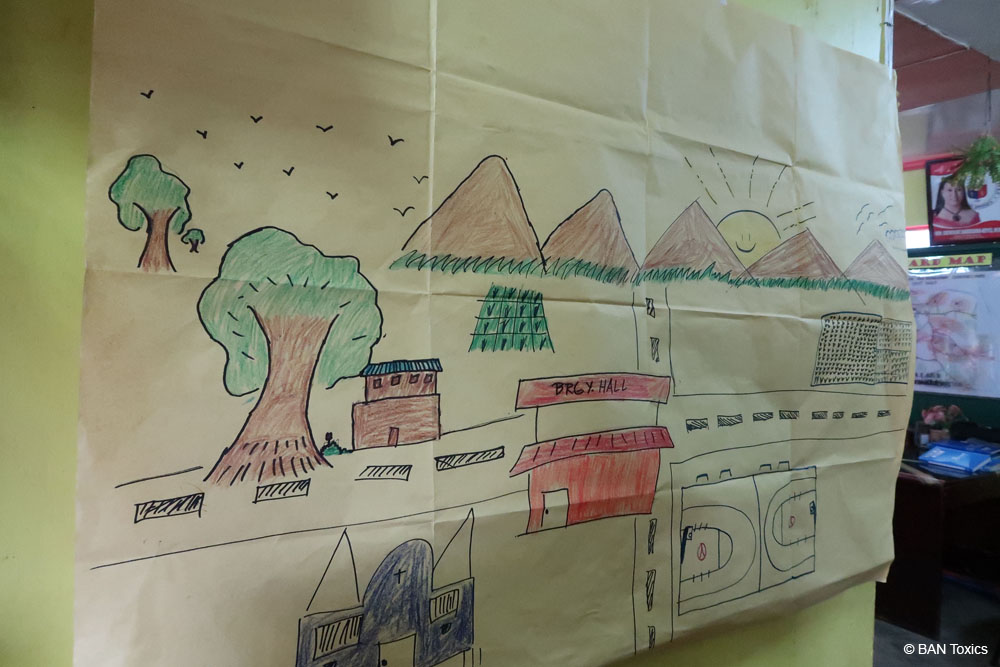

A drawing made by a child during the focus group discussion by BAN Toxics. On October 20, 2016, BAN Toxics held a focus group discussion with the youth from Sta. Rosa Sur, Camarines Norte to understand the experiences of the youth in the community. © BAN Toxics

In these communities, nature’s greens and browns were everywhere: undulating land scattered with pineapple plants and coconut trees, nipa huts with simple little gardens, wet mud edging around pretty little flowerbeds. The morning sun painted everything with a subtle yellow glow. The chalk white clouds seemed close enough to jump for.

This is the small entrance of the mining shaft that goes some 20-30 feet down. On October 19, 2016, BAN Toxics visited a mining site in Labo, Camarines Norte to see the processes and challenges of a normal mining site in the area. © BAN Toxics

I also faced the intimidating pitch black at the mouth of a vertical mining shaft. Inside the 20-foot shaft was the oppressive, disquieting black that seemed to envelop me as I descended into the claustrophobic mine. The dark slithered around the edges of the light coming from my smartphone.

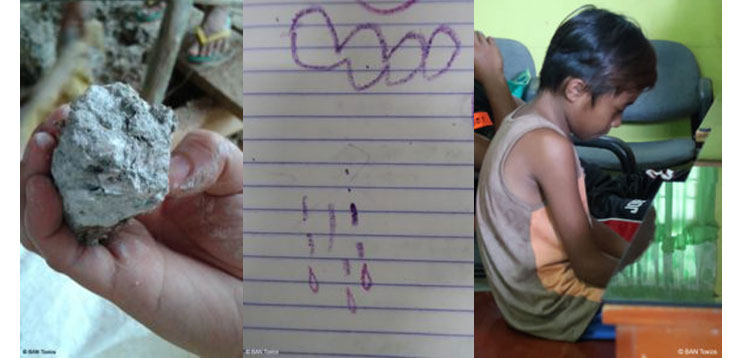

At the bottom of the shaft, ashy gray sludge clung to my boots. Later on, this sludge hardened and revealed glittery amber specks that teased the presence of precious metal, of gold.

These colors, while beautiful, threatening or mesmerizing, did not capture my attention the most. What did was the purple rain.

The rain was made by Emil (not real name), an 11-year-old boy from the town of Santa Rosa Sur. I sat beside him as he drew his rain with smooth and careful strokes, a purple shower coming from a purple cloud.

Jimbea Lucino leads the participants in an exercise to imagine their entire community and all the resources found there. On October 20, 2016, BAN Toxics held a focus group discussion with the youth from Sta. Rosa Sur, Camarines Norte to understand the experiences of the youth in the community. © BAN Toxics

Emil was a participant in a focus group discussion meant to capture the views and experiences of children in this mining community. Shy and unsure of himself, Emil was hesitant to take part in a drawing activity and shrank into his beige and orange sando as children started sketching. Some older kids teased him into participating, and the persistent taunting made him cry. That’s how I first met him… face buried in his hands to hide his silent tears.

I approached him and told him not to pay attention to the other kids. I handed him several crayons and asked him to pick the best-looking color. He quickly pointed at the purple crayon. I drew a cloud on a notebook and asked him to copy it. He said he couldn’t but tried anyway, a show of subtle courage. Then, he drew droplets falling from his cloud… his purple rain. I asked him to add clouds to the other children’s artwork. Off he went, crayons in hand, adding several puffs of white.

For all his shyness, he was equally strong. He continued to prove this as I got to know him more. Emil does not know how to write, so I helped him through the written part of the other activities. That’s how I learned about his very young life:

He is the third oldest child in the family. He was forced to stop school in order to take care of his younger siblings and allow his older siblings to continue studying. Every day he prepares meals for his family, washes the dishes, gathers water, watches over his young siblings alone, rinses everyone’s muddy slippers and cleans their home.

He also takes part in the work of his father, a miner. Emil sometimes helps in sluicing the muck from mining shafts and in panning for gold. His slight frame belies his resolve. His shoulders have carried the weight of adult responsibilities for his family. His favorite color might be purple, but his life is likely to revolve around gold.

Purple and gold are colors of royalty and prosperity. How ironic that for a land rich in precious metals, economic well-being is limited in the community of Santa Rosa Sur. Gold seems to leave the community soon after it is unearthed and blesses only a few with permanent wealth. Gold is like a tantalizing mirage of riches for the community, one that fades away quickly, leaving mostly the challenges of poverty in small-scale mining.

Emil and his community have been blessed with a wide spectrum of vibrant and precious natural resources. They should be able to utilize, enrich and most importantly safeguard these resources as a community. If they are able to do these, then surely Emil and the rest of Santa Rosa Sur’s children can have a brighter, more colorful future.

BAN Toxics works in communities such as Santa Rosa Sur in Camarines Norte to promote responsible artisanal and small-scale mining through mercury-free methods and the establishment of sustainable mining business models. BAN Toxics also seeks to work with the community in improving local capacity and organizing community members, women and children.

This piece was written by Lean P. Lava, BAN Toxics Communications Officer.